Allienated Lawyers Seeking And Getting

Counsel In Making The Transition To Other Careers.

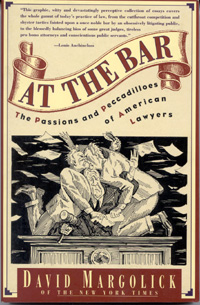

By David Margolick

At The Bar, reprinted from The New York Times

|

Fidel Castro did it. Francis Scott Key and Tony LaRussa did it. Paul Robeson and Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky did it. Even Cole Porter did it. Let's do it. Let's leave the law. It's a song many seem to be singing these days. And Celia Paul, a 44 year-old career counselor to disaffected lawyers, is leading the chorus. There is no doubt that many lawyers, particularly young ones, are alienated labor. Whatever prompted them to enter the profession - idealism, status, intellectual curiosity, skills training, the lack of a clear alternative - many are appalled by what they've found. As many people are now abandoning the law annually - roughly 40,000 - as entering it. |

|

More than anyone else, Ms. Paul guides such lawyers along the underground railroad to other careers. She has discovered that not only is disillusionment widespread, but also it is lucrative. In the last year, she advised nearly 1,000 disgruntled lawyers, many of whom paid her $1,200 for her wisdom.

This week, nearly 100 of them attended her "Lawyers in Transition" workshops in New Jersey, Long Island and New York. They had seen her advertisement in were finally facing up to the reckoning so many of them had put off for so long.

The phenomenon is not confined to New York. Foundering, floundering lawyers have established self-help grounds in San Francisco and Seattle. The founder of the Seattle program, Deborah Arron, lapsed lawyer, author of "Running from the Law: Why Good Lawyers Are Getting Out of the Legal System," soon to be published, said 10 percent of the local bar had participated in her seminars and workshops.

Ms. Paul, who first taught a course called "Lawyers, You're Not Stuck" at the Learning Annex five years ago, will soon take her show to Tampa, Miami and Albuquerque. She is even registering the phrase "Lawyers in Transition" with the United States Patents and Trademarks Office, giving it the same protections as "Put a Tiger in Your Tank."

As they field into the Princeton Club Wednesday night, Ms Paul's latest crop of clients were somber and tense, befitting people coming from jobs they could not abide. But like anyone trying to shed a noxious habit, they quickly discovered the cathartic power of communal confession.

As they introduced themselves, first names only, they talked of professional stagnation, personal stultification, pressure to bill long hours, tedium, sexism, degradation, infantilization and gamesmanship.

"Quite honestly, I feel guilty charging clients $185 an hour," Tom said. "Half of what I do is very silly. I get to the point of saying 'lawyers are ridiculous,' and then I realize I'm one of them." Nancy Lamented about how she was "just making rich people richer."

They then filled out forms, listing their skills, values and job preferences. "Write several metaphors that express your feelings about law," one exercise directs. "Example: Working in law is like a nightmare: you'd like to get out of it but you need the sleep."

Most of the lawyers had been out of school only a few years. Few were from very top firms, were unhappy associates usually fend for themselves. The most agitated were the litigators - some of whom, Ms. Paul says, throw up nearly every morning before coming to work - while bored corporate lawyers were more prevalent. More than half were women. All have other loves.

"People ask me: 'How can you work with lawyers all day? They're so boring,'" Ms. Paul said. "But my clients are into a lot of different things."

Next month, the lawyers will hear from others who have already made the transition, like Craig Davidson, who directs the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation; Martin Stone, an originator of television's "Howdy Doody"; and Andrea Lachman, co-owner of Mike's American Bar & Grill in Manhattan.

Ms. Lachman endured seven years at three law firms, including one of Ms. Paul's most fertile spawning grounds, New York's Rosen-man & Colin. Now she spends her days serving up "killer-hot chili" and "arugula and cucumber salad with frizzled corn tortillas."

"A month after I stopped practicing law, I realize I'd had a knot in my stomach all those years, and that it had suddenly gone," she said, as Patsy Cline crooned "I Go to Pieces" in background.

"Financially I'm not as well off now, but emotionally I'm far ahead," she continued. "I got married and had a child. And I felt tremendous professional satisfaction. Everything just fell into place." Patsy Cline was still on the jukebox. Only now she was singing "Sweet Dreams."

Enrollment in Ms. Paul's workshops has doubled in the past five years. Increasingly, participating lawyers tend to older and, as the employment market has tightened, driven less by existential angst than economic necessity: that is, having been told to leave, they're being forced to find something